這個思考模式鼓勵學生在一個特定的系統裡思考不同人物的觀點。其目標是幫助學生理解系統裡的不同角色,他們會用什麼形式去表達感受以及對系統裡其他人物和事物的關心。這個思考模式引導學生從多角度去提出問題並表達觀點。

Critical Sensitivity to Design Questions

A set of questions for students and educators that support critical inquiry and awareness when approaching human-designed objects and systems.

“換位思考” 的思考模式

這個思考模式鼓勵學生在一個特定的系統裡思考不同人物的觀點。其目標是幫助學生理解系統裡的不同角色,他們會用什麼形式去表達感受以及對系統裡其他人物和事物的關心。這個思考模式引導學生從多角度去提出問題並表達觀點。

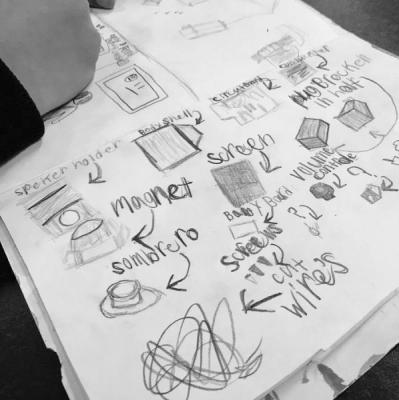

Observational Drawing

This practice allows learners to notice features of an object that they may not have the vocabulary to fully describe yet. By doing several sketches, learners have the chance to engage in perspective taking and to see details they might miss at first glance.

How Can Understanding What We Value as Educators Shape What We Assess in Our Classrooms?

What do we want our learners to be like when they leave our classrooms at the end of the year? What does authentic learning look like in a maker-centered classroom? Your response to these questions might be an indicator of what type of learning you value as a teacher. Inspired by Carlina Rinaldi and her writing on the relationship between documentation and assessment, we used these questions to identify what types of learning or dispositions teachers value most within their contexts. Think of it as a lens for looking at learning. What we quickly realized is that the values educators bring to their work have implications connected to assessment.

Participatory Creativity: Introducing Access and Equity to the Creative Classroom

Participatory Creativity: Introducing Access and Equity to the Creative Classroom presents a systems-based approach to examining creativity in education that aims to make participating in invention and innovation accessible to all students. Moving beyond the gifted-versus-ungifted debate present in many of today’s classrooms, the book’s inclusive framework situates creativity as a participatory and socially distributed process. The core principle of the book is that individuals are not creative, ideas are creative, and that there are multiple ways for a variety of individuals to participate in the development of creative ideas. This dynamic reframing of invention and innovation provides strategies for teachers, curriculum designers, policymakers, researchers, and others who seek to develop a more equitable approach towards establishing creative learning experiences in various educational settings.

Parts, Purposes, Complexities

This thinking routine helps learners slow down and make careful, detailed observations by encouraging them to look beyond the obvious features of an object or system. This thinking routine helps stimulate curiosity, raises questions, and surfaces areas for further inquiry.

When a Ship is not a Ship—It’s a Sabre-toothed Cat! A Story of Maker Empowerment and Collective Agency

Ilya Pratt, AbD Oakland Leadership Team member and Design+Make+Engage program director at Park Day School, tells a tale of maker empowerment and collective agency through the story of Kyle and the saber-toothed cat.

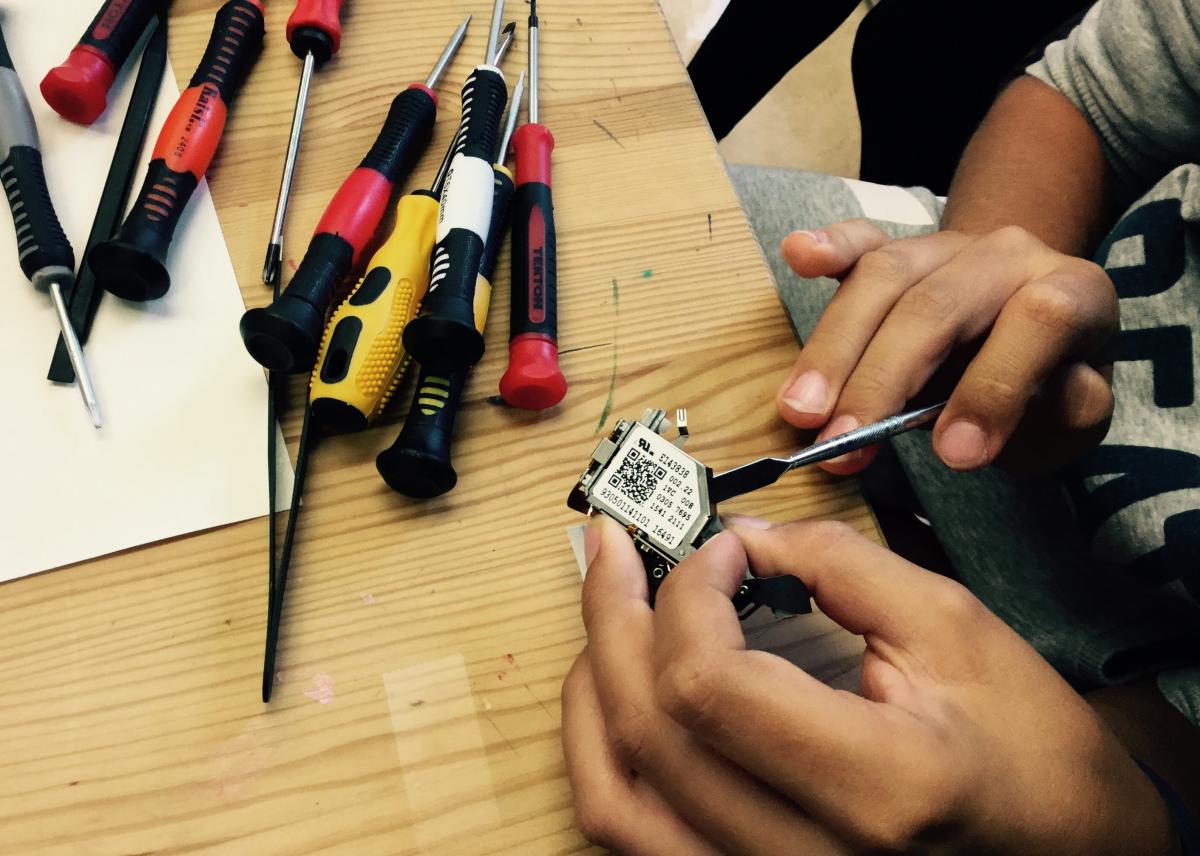

A Take Apart Toolkit: What we learn from unmaking

This piece is the first in a series of Field Notes which can be read as a Take Apart Toolkit of sorts, including how to use Take Aparts to engage in deep analysis, to increase accessibility, to explore the complexity of less tangible objects and systems, and more.

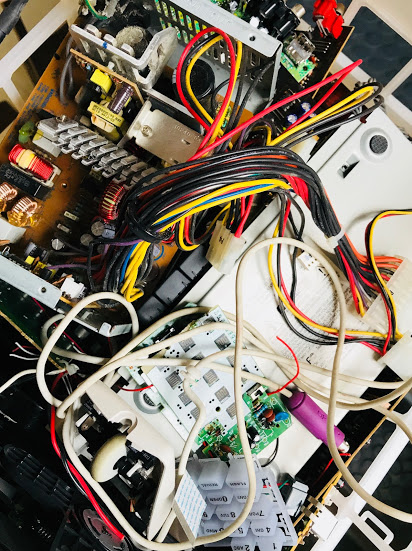

Cracking the case of a computer always inspires a small gasp—an intake of breath that is part fear and part wonder. And it really is beautiful in there.

For that matter, so are the guts of a blender or a blow dryer or an FM radio. When I first started using Take Apart practices in the classroom, it was for the simple unwrapping of the incredible miniature landscape inside of the familiar objects that we think we understand most intimately. The view from the inside is a powerful and nearly instantaneous entrypoint into what Agency by Design names a sensitivity to design—that the world around us is designed and made by humans like us, and can be remade, too.

For that matter, so are the guts of a blender or a blow dryer or an FM radio. When I first started using Take Apart practices in the classroom, it was for the simple unwrapping of the incredible miniature landscape inside of the familiar objects that we think we understand most intimately. The view from the inside is a powerful and nearly instantaneous entrypoint into what Agency by Design names a sensitivity to design—that the world around us is designed and made by humans like us, and can be remade, too.

Over time, I came to think of a Take Apart a perfect first dip into maker-centered learning for learners of any age or context because it requires very little prior knowledge. When I’m guiding a group of learners, I like to ask: Look at the object in front of you—do you know its name? Have you ever used it? Most of us can stare down a clock with some level of confidence and firsthand experience. We have a connection to an object we recognize and ready access to what we already know about how it is used, some alternative forms it may have, and even some ideas about how it works. We have memories that may connect it to our home, the Kindergarten teacher who taught us how to tell time, the last clock we touched. A Take Apart has an emotional locomotion that is hard to resist.

A first, essential step is looking closely—slowly observing and reflecting on the whole. One of the key requirements of a Take Apart, and one that I share with learners, is this important permission: You will not be asked to put it back together. You do not need to preserve it. Once the clock is really Taken Apart, it does not go back together, literally or conceptually. It is a plastic rain poncho that can never be stuffed back into its perfect tiny pouch. When we unpack the parts and complications of the clock—when we explore complexity—our understanding of it balloons out dimensionally.

A first, essential step is looking closely—slowly observing and reflecting on the whole. One of the key requirements of a Take Apart, and one that I share with learners, is this important permission: You will not be asked to put it back together. You do not need to preserve it. Once the clock is really Taken Apart, it does not go back together, literally or conceptually. It is a plastic rain poncho that can never be stuffed back into its perfect tiny pouch. When we unpack the parts and complications of the clock—when we explore complexity—our understanding of it balloons out dimensionally.

Permission to break things is a visceral release, and the small shock of cracking the case of a clock marks that crystal moment of transgression. “No going back now,” some learners might say, or “Is this what I’m supposed to do?” They have entered forbidden territory.

The real processing begins when learners' hands are deep in the guts of the clock and a flurry of questions and inferences rise out of their inherent curiosity. It can get wild in there, and conversations and observations help make order and meaning of what they find. I like to prompt, What do you see? What words or numbers can you find? How are things connected? How does it work to move the hands? As pieces start to come out onto the table, I ask: Sort them in a way that makes sense to you. Is it the way they fit together on the inside? Is it by size or color? What way explains the clock best?

When everything is out, when it is arranged as a representation of our understanding of the clock, it has changed irreversibly. It is broken, for sure, but it is also now physically and conceptually larger than it has ever been. Reflection can make visible how learners’ understandings of the clock and their thinking about it have grown. They can teach what they have learned, or explain a moment of surprise where what they thought they knew about the clock was upended. I often invite my students to consider the following: What was hard about taking it apart, physically or emotionally—and what does that mean? What was hard about explaining its workings? What puzzles remain?

Then finding opportunity becomes a natural next step. Often, learners will ask me if they can keep a piece of this clock. I might ask: Why this piece? What do you want to do with it? What should be thrown away, and what is just too interesting?

In the past year, the Making Across the Curriculum project at Washington International School has supported our faculty to dig into an exploration of what Take Apart practices might look like in a classroom. The curiosity and enthusiasm of students during a Take Apart is often the most obvious impact, but we are also trying to identify more subtle evidence of student understanding.